Tales from my Travels

Stories from around the globe

“Exploration is the essence of the human spirit.”

— Frank Borman

Trapped in Obod Cave

As featured in Damien Lewis’ novel - SAS Great Escapes Two.

“I slipped between two boulders, tearing my arms and legs as I fell 10… 12 feet… maybe more…”

"Your book saved my life."

These were the five chosen words in the subject line of my email to best-selling author Damien Lewis months after my ill fated expedition to the Montenegrin forest.

Meanwhile, the words chosen in a stranger’s Google review, which proved to be the catalyst to my experience, were as follows… "Be sure to get to the bottom (it will not work without a flashlight), there is an underground river."

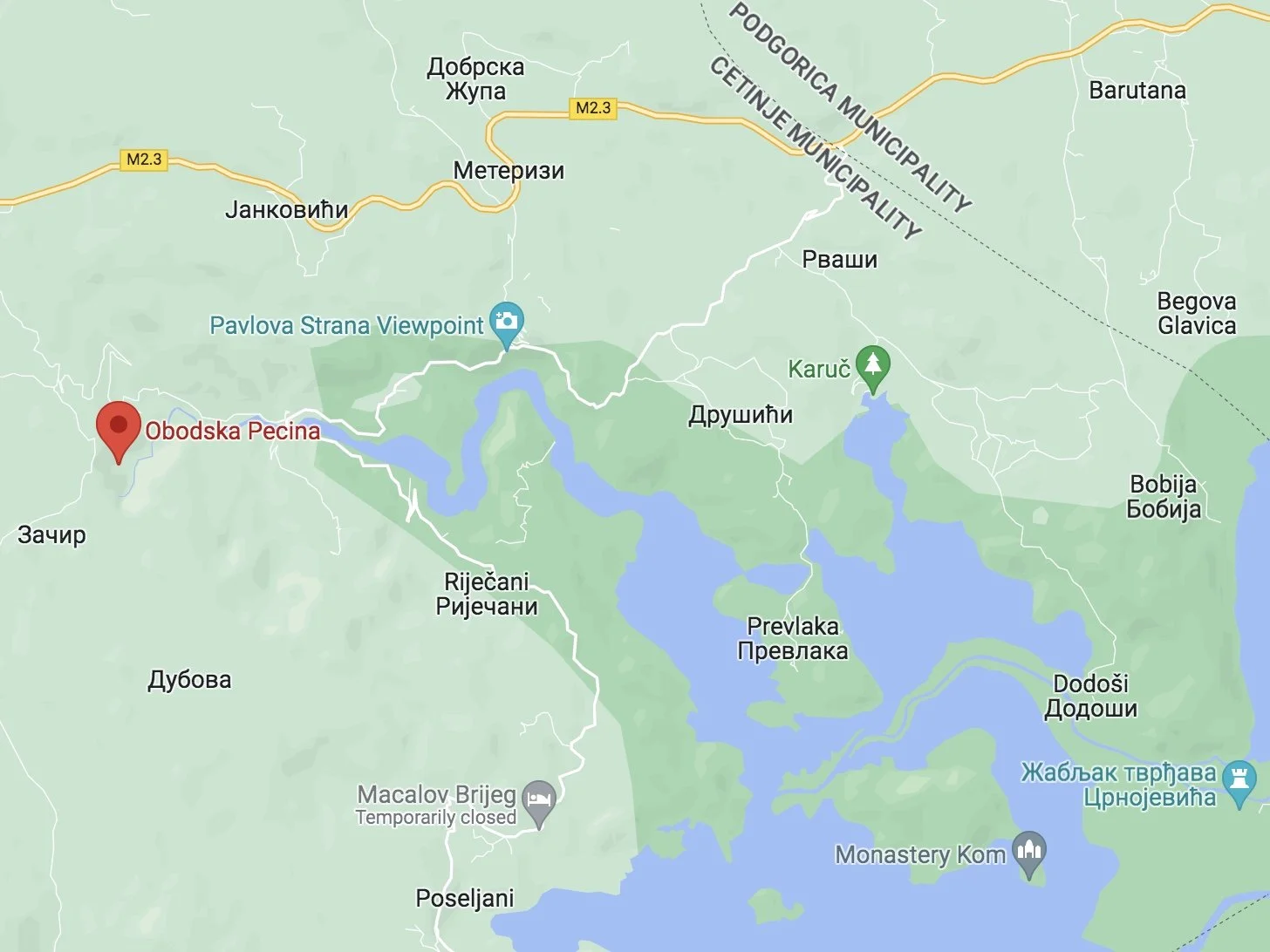

Armed with the paltry torch on my iPhone, a book, a bag of dates and a tin of sardines, I headed for Obod Cave near Rijeka Crnojević, hidden in the deserted and verdant hills surrounding Lake Skadar.

With my reckless and adventurous personality as it is, I couldn’t shake the underground river from the forefront of my mind as I hiked the 6 km to the cave. I snapped a few photos at the entrance to the cave, as I started to feel slightly isolated having not seen a soul for hours. I ventured a little further in, as I have done in many a cave in my life, with the light from the entrance still in sight. Ahead of me it began to drop off quite sharply as I descended into the Stygian darkness, with the deafening screeching of a thousand bats whirling above me beginning to drown my senses. Adrenaline coursed through me as I heard the first faint trickle of water beckoning from the depths. The sound gradually began to get louder as I went deeper and deeper. The angel on my shoulder urged me to turn back; but I pressed onwards to the gushing river, seemingly nearing but all the while remaining tantalisingly out of reach. An hour passed before I reached it, filled up my bottle for the return journey and contemplated life a mile underground, turning my phone torch off momentarily to allow the darkness to envelop me.

I turned around and made for the exit. 45 minutes of ascent later, I reached a dead end. I calmly turned around, rationalising that there must be two tunnels and I just picked the wrong one. Finding myself at the river anew, I made for another tunnel. As time passed, it narrowed and narrowed until I could barely ascend any further. Knowing my way in had never become so tight, I started to panic and frantically retraced my steps to the river, faster and faster until I slipped between two boulders, tearing my arms and legs as I fell 10…12 feet… maybe more. Crumpled in a heap, I thought to myself, had I hit my head in the fall, that would have been my resting place for evermore. Thought, at the time, that was of little consolation to me, as the thoughts began to creep in that I was never making it out regardless. I was hopelessly lost. Water seemed to be gushing from every angle, from behind every boulder, but the river was nowhere to be seen. At this point, I convinced myself that I would die in that cave, and my body would never be recovered.

As I attempted to steady my breathing, I thought of my parents and my siblings. I envisioned the police knocking on the door at home to inform them I wasn’t coming back. My muddled thoughts also turned to a German girl I’d met the day before, and somewhat fell for, who’d invited me to her 30th birthday in the Berlin countryside in August. My greatest sadness as I sat there was the thought I’d never see what my future children might be like, so I painted a picture of them in my head.

Somewhat sobered up and spurred on by such thoughts, I looked in my pack to see what I had. As I ate a few dates and the tin of sardines, staring blankly into the darkness, I thought of Theseus and the Minotaur and Ariadne’s ball of thread. He managed to get out. Theseus led my mind to Hansel and Gretel. They managed to get out. I mused with the idea of leaving a trail of dates, hoping nothing would be down there to eat them as the birds foiled Hansel and Gretel’s breadcrumb plan. Just as I concluded that the dates would in fact be camouflaged on the muddied rocks, I caught sight of the white pages of my book in the bottom of my bag.

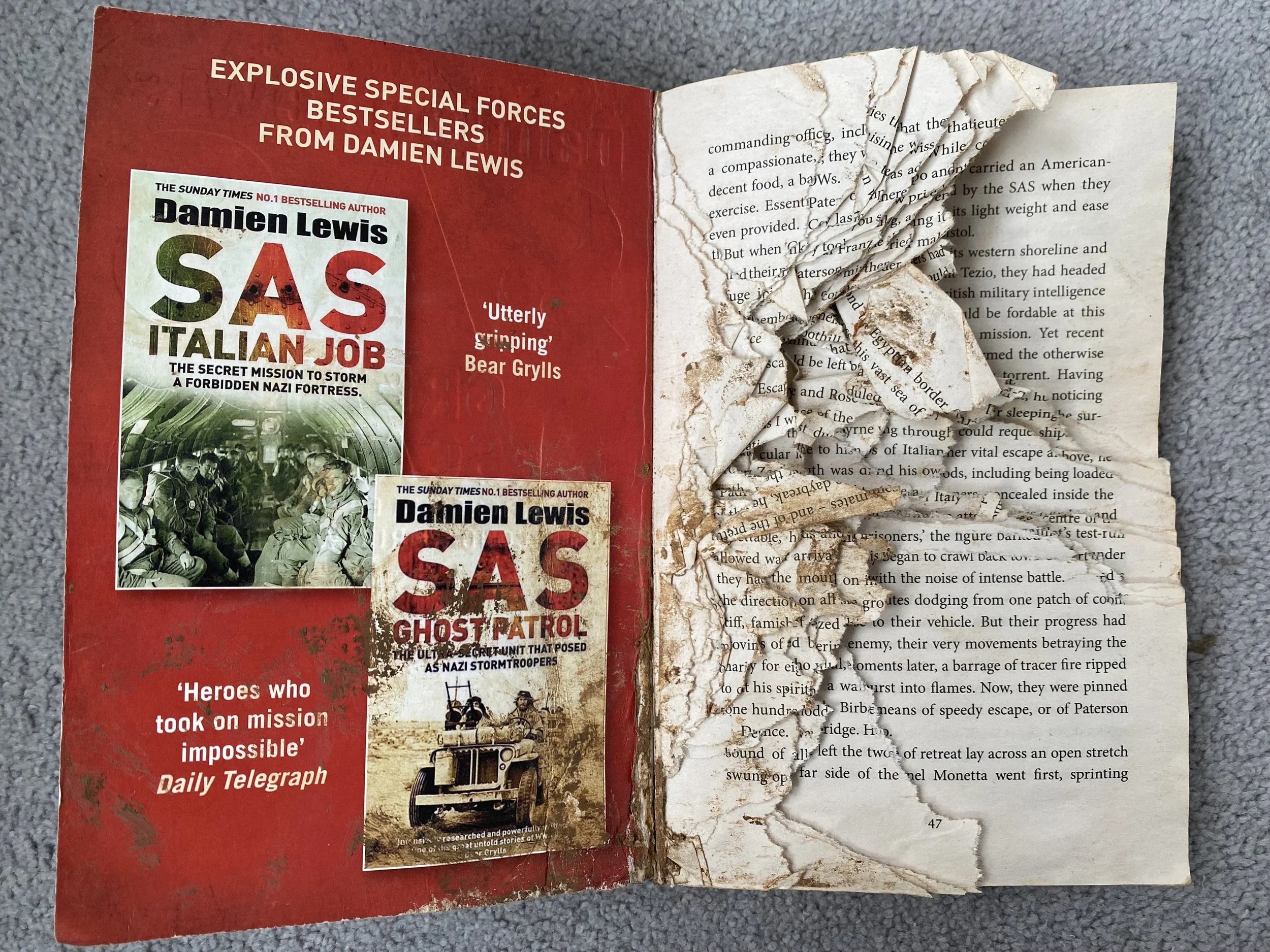

Tearing the first page or two into a trail quickly led me back to the all too familiar river below, as I felt a glimmer of hope trickle into my bones. Shining my phone torch onto the cover, I was struck by the cruel irony of the book that I was using to make my cave escape… none other than SAS Seven Great Escapes. Despite historically only going to church at Easter and at Christmas, I furiously began to pray, begging that I be granted one last chance to emerge unscathed from the umpteenth life threatening situation I’d got myself into on my travels.

I continued tearing page after page into little pieces as I chose another angle away from the river, placing each shred of writing with purpose, on a visible part of each boulder I traversed over, pressing it gently into the mud to prevent it from being blown away by some mysterious underground breeze.

Ascent three, my first using the book, failed.

Ascent four led me to another dead end.

Ascent five… same result.

Each time I returned to the very same point where I had filled up my water bottle hours earlier. Before long I was surrounded by the beginnings of paper pathways forming a clock face around me. 9 to 11 o’clock was as yet an untried route. I fiercely repressed any building hopes of escape as they had led to such crushing disappointment on every attempt so far. Instead, I resigned myself to my fate but tried the last route nevertheless. By this point I felt less and less in touch with my senses and scarcely tell which way was up or down.

I blindly pressed forward and upwards for 20… 30 minutes. I strained my ears… was that the bats I could hear? Since the initial descent there had been just one or two fluttering around, but the sound had gone long ago. I moved faster, every boulder simultaneously familiar but strange. The tunnel turned one way and the other as the squeaking grew and the water became a distant murmur.

As I looked up from my path, I saw a faint white jagged outline on the cave wall in the distance. Such was my state of desperation and disorientation after 7 hours underground, hallucinations had begun to fog my vision. Instead of the white outline representing the shadow of the entrance shining down the tunnel from the right and hitting the wall, I instead saw a snowdrift. Every sinew of my being gave up and strained to turn back into the depths of the cave. But deep down, something told me I’d tried every other way and compelled me to go on, repeating that fact over and over in my head.

When I reached the shadow, placed the final piece of my path and turned to see the exit 50 metres to my right, I fell to my knees and wept until I could no longer, my body convulsing in disbelief at my survival.

When I eventually returned to the village from whence I came, caked in mud and blood, the woman who organised the boat tours looked increasingly shocked as she approached me on the shore of the lake, with her first question being, ‘Have you been attacked by a bear?’

As seen on Daily Mail Online: Link to Article.

Kidnapped in Baku

“My tired, bloodshot eyes scanned the carriage for any sign of my pursuer…”

A peaceful kidnapping in Baku

I arrived in Baku on the 26th May 2019, after a gruelling, sleep-deprived 4,000km journey from Palermo, Sicily, 2 days before the Europa League Final between Chelsea and Arsenal. At lunchtime on that same day, I was abducted by Islamic fundamentalists, although I wouldn’t know it until later that evening.

One week previously, I had organised to stay with an Azerbaijani family for my 3 nights in Baku through the Couchsurfing app, and was due to meet my host that evening. That left me with about 7 hours to kill and so I decided to open the ‘hangouts’ section of the app, hoping to meet a local to show me round. I quickly organised to meet with 21-year-old Abdul, who was, in his own words, ‘looking to meet English football fans and show them the best of [his] wonderful city.’

We went for lunch, where he introduced me to all the local delicacies, including dolma – fresh meat and stuffing wrapped in vine leaves, and ayran – a cold yoghurt drink mixed with salt and herbs. After telling me a little about his country and his religion, Abdul invited me to go for tea at his house. I was not yet due to meet my host and so politely accepted, as the English do.

Little did I know at the time, the journey to his house involved getting the Metro to the last stop on the line, a suburb called Nardaran. He led me for 25-minutes as we navigated a dense network of winding alleyways, passing crumbling abandoned buildings, burnt out skeletons of cars and elderly locals smoking hookah.

We finally arrived at Abdul’s home, in a collection of soaring tower-blocks with a bare courtyard in the middle, where mothers pushed children on rusted swings whilst others kicked a football against a red painted goal on the wall. Abdul lived on the top floor – so we took the lift. Inside the dishevelled tin box, there were no buttons, just lumps of metal where they should have been, surrounded by naked, tangled multicoloured wires. It creaked

up to floor 17 and we entered his numberless apartment, where I watched Abdul and his housemates pray for the first time.

Abdul then invited me to ‘a party’ at his friend’s house that evening. My curious nature got the better of me and I went. Though it was not to be a party at all, but a prayer gathering with Abdul’s ‘brothers’, conducted by their Supreme Leader, as he referred to him, clad in his white skullcap and traditional dress. The gathering began with a meal, where all 16 of us sat cross-legged in a circle on the floor. I was told to sit next to Abdul and opposite the Supreme Leader, as they were the only two who spoke English. The rest were left to chit chat uncomfortably in Arabic around me, my 1 year of classes at school not sufficing to understand a single word.

Before we finished eating, my phone was taken, and the entirety of the Quran was downloaded onto it in English; I was gifted a book entitled ‘The Fundamental teachings of Islam’; and the Supreme Leader told me, ‘you are one of us now’. It was then that I realised that I wouldn’t be allowed to leave.

After dinner, I was forced to learn the essential Arabic phrases used in their prayers and to pray alongside them. I hadn’t slept for over 48 hours but from the leader’s tone of voice, I knew I couldn’t refuse. For two hours I prayed, knee to knee with Abdul, nervously clutching a rosary in my clammy hands. I insisted I had to leave to meet my host, but I was told I must stay with them until I had fully converted to Islam.

Exhausted as I was, I didn’t sleep a wink that night. I lay awake, trapped in two minds, flitting between what my captors might do to me and whether I would make it to the fabled match I had taken 3 flights and a 19-hour bus to watch. As the faint light of the moon crept through the cracks in the window, flashes of front-page news headlines concerning Isis began to invade my thoughts. My stomach turned over and my breath quickened as I eavesdropped the group’s muffled Arabic mutterings next-door and it dawned on me that I might be next. Unaware of the address, unwilling to alert my parents of my abduction, and unable to make any calls, I desperately sent my pinned location, exact to an all too vague 200 metres, to a father and son I had met on the bus, in the vain hope they might be able to help me. No response.

At 5am I was ushered out of bed by Abdul, whose friendly demeanour from the day before had turned cold, for morning prayers. The Supreme leader then ordered his servant to make me breakfast before sunrise in order to observe Ramadan. I pleaded with him that the match was that evening, but he flatly refused as it would contravene the laws of Islam. With his parting words, he said he had planned a special ceremony for me, and I did not for a second want to find out what it entailed. The servant and I remained in the kitchen, eating in silence alone. It slowly occurred to me that he, Mohammed, was the weak link.

As I looked into Mohammed’s inexperienced eyes, my mind began to wander. I did not know exactly what he believed in, but I understood why he was there. Or at least I thought I did. There he had found a sense of belonging. He had found a family. I found myself questioning whether I would have been more receptive to their attempts to convert me if I did not have a home to go back to. Quickly banishing such thoughts, I managed to convince Mohammed that I was due to meet my English friends before the match. Over Google Translate, I promised him I would return and that they would come looking for me if I didn’t show. He begrudgingly agreed on the condition that he accompany me.

After quietly packing the few belongings I had into my pack, we walked to the Metro station. To my great relief, the station was heaving, but Mohammed wouldn’t leave my side. It was clear to me, though, that it might be my only chance to escape. As the train began to pull in, the sweat trickling down my face from the stifling 40-degree heat, I pushed away from him and jostled through the throngs of commuters, darting into any gap that opened up. I forced myself onto the final carriage and shrunk into a corner, knowing Mohammed was in hot pursuit. The two minutes it took to arrive at the next station were an agonising wait, my tired bloodshot eyes scanning the carriage for any sign of my pursuer. The train slowed, the doors clicked open and I ran for the exit without a backwards glance. As I fled in a petrified blur to the cover of a kiosk, every footstep and every voice I heard belonged to Mohammed. But he was nowhere to be seen.

With my heart still pumping out of my chest, my attentions began to turn, as I looked down at my watch and noticed I had two hours to find alternative accommodation and get to the match. I ended up in an unfinished hostel room with no lock, next to a dormitory of 4 Chinese Chelsea fans who had travelled from Beijing. I grabbed my Arsenal shirt, hid my bag under the bed, and arrived at the stadium 15 minutes before kick-off. In the sea of red and blue flags outside the 70,000 Baku Olympic Stadium, I was overcome by a frightening combination of paranoia and adrenaline as flashing images of my captors wreaked havoc in my head, as I pictured them all around me.

90 minutes later I found myself with my head in my hands, crestfallen, contemplating a cruel 4-1 defeat, whilst an 84-year-old fellow Arsenal fan offered me a few words of wisdom. Such is the beautiful game, that the pain I experienced in that moment banished any thoughts of the harrowing 27-hour ordeal that preceded it and how it all could have

turned out so very differently. What remained in the back of my mind, though, was something the Supreme Leader had told me the night before. Once I had converted to Islam and learned everything I needed to know, he was to send me to his brothers in Paris, Vienna, Berlin and London to fulfil my duty to Allah. The true meaning of this, I hope to never know.

Andata Senza Ritorno

As featured on Student Travel Tips.

“the cracked tarmac of the Sicilian roads, electrified by the heat of summer, traced my adventures like the roots of a towering oak”

Andata senza ritorno: an ode to Sicily

An idol of mine, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, once declared that going to Sicily is better than going to the moon. Whilst I have not yet been lucky enough to experience the latter, I can say with some certainty that it does at least come close. Four months was enough for me to fall incandescently in love with the scorching heat of Sicily and its effervescent people. In fact, my first weekend in Palermo alone, was sufficient to tell me all I needed to know about the islanders, who are always so quick to separate themselves from age-old generalisations of mainland Italy and Italians, and rightly so.

I had barely walked through the gargantuan 16th century doors of Palazzo Lanza Tomasi, which was to be my home for the duration of my stay, when I was whisked away to a villino tucked away on the hill far above the iridescent waves which lapped the glitzy Mondello coast, for Pasquetta – Easter Monday celebrations. What could have been described as a baptism of fire, with my limited Italian serving no apparent use in the face of incessant Sicilian slang, in hindsight resulted to be one of my fondest memories of all. My host Carlo, who did not even know my name until he picked me up that afternoon in his battered red Cinquecento, made me feel entirely central to the Easter festivities which resemble such an intimate and sacred occasion in the Sicilian calendar. Later that same day, Carlo gave in to the pleadings of the football obsessive that I am and dropped me off at the stadium for what was to be a defining match at the climax of Palermo’s Serie B season. Despite arriving halfway through the first half, I desperately circled the locked gates until a security guard came over. After informing him of my ticketless predicament and my aching desire to see the rosanero in action, he handed a ticket through the bars which he had reserved for

his absent son and slipped me into the reverberating cauldron of pink and black noise free of charge. Aimlessly wandering the quickly emptying streets after a tense Palermo victory, I was then invited to a typical gelato in a brioche bun by the boss of a nearby gelateria, who then proceeded to drive me home once he realised I was at the wrong end of the city on a bank holiday, when the buses were most definitely not running. The kindness shown to me that day by Carlo, the guard and my fellow ice-cream loving capo, has, for me, only ever been matched by those whose paths I crossed in remote parts of South America – a continent in which, looking back, I see multiple similarities with Sicily.

Akin to my Pasquetta adventure, the next four months were a blur of sheer excitement and adoration for my senses, interspersed at every turn with bursts of intense colour and fragrant smells, the like of which I had never experienced. Whether I was watching the sun lay to rest from the crumbling roof of the magnificent abandoned lighthouse in Capo Gallo with someone I had just met in the nature reserve, or careering round the perfectly chaotic Palermitan streets with Giorgio on the back of his Yamaha racing bike - the one thing which was always present at the core of each and every experience, was the Sicilian people.

The person who proved to be my roots and my rock throughout, as crazy as she was kind-hearted, was Giorgio’s younger sister, Sofia. During my first week, my Palermitan colleague Asia invited all of our Erasmus cohort to her best friends’ birthday. Whilst everyone before me declined, I cast aside my longing for bed and accompanied Asia to a piazza where the uneven cobbles delicately glowed and notes of questionable Italian pop danced in the muggy night air. In the midst of frenzied gift giving, my ears were blissfully paralysed by the unmistakeable melody of the Spanish

language. I swivelled on a sixpence and asked a taken aback Sofia if she was Spanish. Needless to say, she was not, but in that beautifully spontaneous instant was born an enduring friendship based on the unflinching foundations of Spanish and tequila. And one which might never had existed if it weren’t for my willingness to banish my English inhibitions and mindlessly accept every quirky proposition which came my way.

The lonely days which you experience in a city which is not your own is an inevitability of travel. But it was on these days most of all, when I felt vulnerable and alone, that my phone would ring. Every time it was Sofia, each time with a more ludicrous plan than the last, from sleeping on Mondello beach for her birthday - huddled like new-born puppies alongside 20 of her friends - to privately taking a boat out to explore a network of caves despite our common inability to drive even a go-kart. In fact, driving anything in Palermo represents a near impossible task, with the sea of cars at times appearing to subconsciously zig zag like lizards in the Sahara.

Despite this unfortunate shortcoming, the burning heart of what it means to be Sicilian is so infectious that anyone who spends time there is immediately transformed into the altruistic, accepting and inclusive human being that all of us carry inside us but so rarely show. This was never truer than for a tightly knit group of Senegalese guys I met early on. As I meandered through the dense maze of alleyways in the historic centre, ducking under brightly coloured, breezy washing lines as I went, I came across a dilapidated cage in a stunningly derelict square where my soon-to-be friends were playing football, clad in kits from all over the world. Noticing my Arsenal shirt, they called for me to join, and despite my initial attempts to interact with them in French, their mother tongue, they insisted we speak Italian, or rather, Sicilian. After playing with them twice a week for four months thereafter, I realised that they unequivocally embodied the essence of the fiery, unselfish Sicilian spirit as much as any lifelong resident. In fact, much of the beauty of the island’s identity originates from its wistful ability to seamlessly merge with the international community. Languid evenings are spent on rooftops at bossa nova jazz concerts under silk blankets of stars, whilst South American folk dancers grab you by the hand and twirl you round under the ancient city gates.

In this vein, the person who for me most accurately incarnates Sicily is originally from Venice. It is fair to say that my boss and Duchess of Palma di Montechiaro, Nicoletta, is a force of nature in every sense of the phrase. All that she asks of her piccoli, which translates as ‘little ones’, or interns in standard English, was that we looked after her home and her guests as if they were our own. In return, she took us in as her children. During our first meeting, she remarked at how thin I was and asked whether my parents fed me. Despite my assurances, she messaged me every evening to go to her kitchen, convinced I was unable to cook for myself, and made up delectably simple plates of bread, cheese and homemade soups for me to take back to my flat. She also demonstrated the Sicilians extraordinary capacity for forgiveness, when after one infamous night in the Vucciria with Sofia, I woke up six hours late for work. No words were uttered when she called me into her office that evening, but I knew the importance of regaining the implicit trust which forms the bedrock of any relationship amongst her people.

Now, it is impossible to breathe a word of the Sicilians without a mention to the lifeblood that runs through their veins – food. Each and every person who cooked for me did it with such a warm sense of pride, from Nicoletta to the characterful owner of Bar Bruno, a tiny eatery just a stone’s throw from my home, whose nonna would cook pollo alla palermitana (not Milanese – you only make that mistake once!) and aubergine alla parmigiana day after day. Regardless if it were in the chic Michelin-guide restaurant opposite my residence, or in the nearby cioccolateria adorned with Arabesque tiling, with one bite I became part of their intimate culinary family. The chefs and waiters would call out and wave as I raced past on my favourite bike each day. There were many better bikes at the Palazzo, but I chose mine for its uncanny resemblance to Guido’s steed in La vita è bella, complete with brown leather furnishings and basket.

It is easy to overuse the word family in any discourse about Sicily, but it is impossible to underestimate the profound sense of closeness you are made to feel there. The old man, with leathery wrinkles etched into his skin from the Mediterranean sun and salt, had nothing to gain when he pulled over in Catania to throw me on the back of his rusted sky blue Vespa and race down the seafront to get me to my Daddy Yankee concert. Likewise, the young fisherman from Trapani who took me to the ruins of a decaying tuna factory to climb as he discovered I so love to do. From each of these fleeting adventures, I learnt to be a little more open and a little more free. In four short months, the venerable city of Palermo had become my home, and the cracked tarmac of the Sicilian roads, electrified by the heat of summer, traced my adventures like the roots of an oak tree. The wondrous island of Sicily is an enchanting chaos of possibility, though it is one that can only be truly understood when embraced with the same enigmatic and serendipitous gioia di vivere expressed by all Sicilians as they welcome you into their hearts and homes.